free 3d nude female medieval warriors pictures and drawings.net free

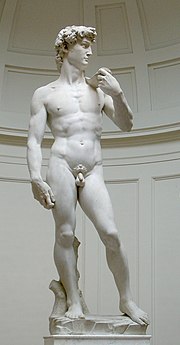

David (1504)

"What spirit is and then empty and bullheaded, that it cannot recognize the fact that the foot is more noble than the shoe, and skin more than beautiful than the garment with which information technology is clothed?"

— Michelangelo[one]

The nude, as a class of visual art that focuses on the unclothed homo figure, is an enduring tradition in Western art.[two] It was a preoccupation of Ancient Greek fine art, and after a semi-dormant period in the Middle Ages returned to a central position with the Renaissance. Unclothed figures often besides play a part in other types of art, such as history painting, including allegorical and religious art, portraiture, or the decorative arts. From prehistory to the primeval civilizations, nude female figures are generally understood to be symbols of fertility or well-being.[3]

In India, the Khajuraho Group of Monuments built between 950 and 1050 CE are known for their erotic sculptures, which comprise about 10% of the temple decorations. Japanese prints are one of the few not-western traditions that can be called nudes, only the action of communal bathing in Japan is portrayed as just some other social activity, without the significance placed upon the lack of article of clothing that exists in the Westward.[iv] Through each era, the nude has reflected changes in cultural attitudes regarding sexuality, gender roles, and social construction.

One ofttimes cited volume on the nude in art history is The Nude: a Study in Platonic Class by Lord Kenneth Clark, offset published in 1956. The introductory chapter makes (though does not originate) the often-quoted distinction between the naked body and the nude.[5] Clark states that to exist naked is to exist deprived of clothes, and implies embarrassment and shame, while a nude, every bit a work of fine art, has no such connotations. This separation of the creative class from the social and cultural issues long remained largely unexamined past classical art historians.

One of the defining characteristics of the modern era in art was the blurring of the line between the naked and the nude. This probable first occurred with the painting The Nude Maja (1797) by Goya, which in 1815 drew the attention of the Spanish Inquisition.[6] The shocking elements were that it showed a item model in a contemporary setting, with pubic hair rather than the smooth perfection of goddesses and nymphs, who returned the gaze of the viewer rather than looking away. Some of the same characteristics were shocking almost 70 years later on when Manet exhibited his Olympia, non because of religious issues, but because of its modernity. Rather than being a timeless Odalisque that could be safely viewed with detachment, Manet's prototype was assumed to be of a prostitute of that time, perhaps referencing the male viewers' own sexual practices.[seven]

Types of depiction [edit]

Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos (1808–1812) past John Vanderlyn. The painting was initially considered likewise sexual for display in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. "Although nudity in art was publicly protested by Americans, Vanderlyn observed that they would pay to come across pictures of which they disapproved."[viii]

The meaning of any image of the unclothed man body depends upon its existence placed in a cultural context. In Western culture, the contexts mostly recognized are art, pornography, and information. Viewers hands identify some images every bit belonging to one category, while other images are ambiguous. The 21st century may have created a quaternary category, the commodified nude, which intentionally uses ambiguity to attract attention for commercial purposes.[9]

With regard to the stardom between art and pornography, Kenneth Clark noted that sexuality was part of the attraction to the nude as a discipline of art, stating "no nude, however abstruse, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling, even though it exist only the faintest shadow—and if information technology does non do so it is bad fine art and false morals". Co-ordinate to Clark, the explicit temple sculptures of tenth-century India "are dandy works of art considering their eroticism is function of their whole philosophy". Bully art can contain significant sexual content without being obscene.[10]

Nonetheless, in the United States nudity in art has sometimes been a controversial discipline when public funding and brandish in certain venues brings the work to the attention of the general public.[xi] Puritan history continues to touch the selection of artwork shown in museums and galleries. At the aforementioned fourth dimension that any nude may be suspect in the view of many patrons and the public, art critics may reject work that is not cut border.[12] Relatively tame nudes tend to exist shown in museums, while works with daze value are shown in commercial galleries. The art world has devalued simple beauty and pleasure, although these values are nowadays in art from the past and in some contemporary works.[thirteen] [14]

When school groups visit museums, at that place are inevitable questions that teachers or tour leaders must be prepared to answer. The basic advice is to requite matter-of-fact answers emphasizing the differences betwixt fine art and other images, the universality of the human body, and the values and emotions expressed in the works.[15]

Art historian and writer Frances Borzello writes that contemporary artists are no longer interested in the ideals and traditions of the past, but confront the viewer with all the sexuality, discomfort and feet that the unclothed torso may express, mayhap eliminating the distinction between the naked and the nude.[sixteen] Performance art takes the final footstep by presenting bodily naked bodies as a piece of work of art.[17]

History [edit]

The nude dates to the commencement of fine art with the female figures chosen Venus figurines from the Late Stone Age. In early historical times similar images represented fertility deities.[18] When surveying the literature on the nude in art, there are differences between defining nakedness every bit the complete absenteeism of vesture versus other states of undress. In early Christian art, particularly in references to images of Jesus, partial wearing apparel (a loincloth) was described as nakedness.[19]

Mesopotamia and Aboriginal Egypt [edit]

The nude in Babylon and Egypt

-

-

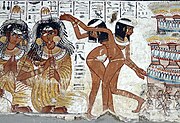

Dancers and Flutists, Thebes (c. 1400 BCE)

Nude images in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt reflect the attitudes toward nudity in these societies. At the time, existence naked in social situations was a source of great embarrassment for anyone with college social status – this was not due to the connectedness between nudity and sexual impropriety, but rather it existence indicative of low status or disgrace.[xx] : 127 Not-sexual, or functional nudity was common in early civilizations due to the climate. Children were generally naked until puberty, and public baths were attended nude past mixed gender groups. Those with low status – non only slaves – might be naked or, when clothed, would disrobe when necessary for strenuous work. Dancers, musicians, and acrobats would be nude while performing. Many nude images depicted these activities. Other nude images were symbolic, idealized images of warriors and goddesses; while gods where shown dressed to indicate their status.[20] : 144 The figure depicted in the Burney Relief could exist an aspect of the goddess Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sexual dear and war.[21] However, her bird-feet and accompanying owls accept suggested to some a connection with Lilitu (called Lilith in the Bible), though seemingly not the usual demonic Lilitu.[22]

Ancient Greece [edit]

Nudity in Greek life was the exception in the ancient world. What had begun as a male initiation rite in the eighth century BCE became a "costume" in the Classical period. Complete nudity separated the civilized Greeks from the "barbarians" including Hebrews, Etruscans, and Gauls.[23]

The primeval Greek sculpture, from the early Statuary Age Cycladic civilisation consists mainly of stylized male figures who are presumably nude. This is certainly the case for the kouros, a big standing effigy of a male person nude that was the mainstay of Archaic Greek sculpture. These commencement realistic sculptures of nude males draw nude youths who stand rigidly posed with 1 pes forrad. Past the fifth century BCE, Greek sculptors' mastery of anatomy resulted in greater naturalness and more varied poses. An important innovation was contrapposto—the asymmetrical posture of a figure continuing with 1 leg bearing the trunk's weight and the other relaxed. An early example of this is Polykleitos' sculpture Doryphoros (c. 440 BCE).[24]

The Greek goddesses were initially sculpted with drapery rather than nude. The start gratis-continuing, life-sized sculpture of an entirely nude woman was the Aphrodite of Cnidus created c. 360–340 BCE past Praxiteles.[24] The female nude became much more common in the after Hellenistic catamenia. In the convention of heroic nudity, gods and heroes were shown nude, while ordinary mortals were less probable to be so, though athletes and warriors in combat were often depicted nude. The nudes of Greco-Roman art are conceptually perfected ideal persons, each ane a vision of wellness, youth, geometric clarity, and organic equilibrium.[xix] Kenneth Clark considered idealization the hallmark of true nudes, as opposed to more descriptive and less artful figures that he considered merely naked. His emphasis on idealization points up an essential event: seductive and appealing as nudes in art may exist, they are meant to stir the listen equally well as the passions.[xix]

-

-

The Marathon Boy (4th century BCE) bronze statue, perchance by Praxiteles

Asian art [edit]

Non-Western traditions of depicting nudes come up from India and Japan, simply the nude does non form an important aspect of Chinese fine art.[25] Temple sculptures and cave paintings, some very explicit, are part of the Hindu tradition of the value of sexuality, and every bit in many warm climates partial or complete nudity was common in everyday life. Japan had a tradition of mixed communal bathing that existed until recently, and was often portrayed in woodcut prints.

In the early twentieth century, artists in the Arab earth used nudity in works that addressed their emergence from colonialism into a modern globe.[26]

-

Kandariya Mahadev Temple in Khajuraho, Bharat (1050)

-

Adult female putting on her clothes (1775), unknown Indian artist

-

Yuami (1915), Hashiguchi Goyô

Middle Ages [edit]

Early Middle Ages [edit]

Christian attitudes cast doubt on the value of the human trunk, and the Christian accent on chastity and celibacy further discouraged depictions of nakedness, even in the few surviving Early Medieval survivals of secular art. Completely unclothed figures are rare in medieval art, the notable exceptions being Adam and Eve equally recorded in the Book of Genesis and the damned in Last Judgement scenes anticipating the Sistine Chapel renderings. With these exceptions, the platonic forms of Greco-Roman nudes became largely lost, transformed into symbols of shame and sin, weakness and defenselessness.[27] This was true non only in Western Europe, merely also in Byzantine art.[28] Increasingly, Christ was shown largely naked in scenes of his Passion, especially the Crucifixion,[29] and even when glorified in heaven, to allow him to display the wounds his sufferings had involved. The Nursing Madonna and naked "Penitent Mary Magdalene", as well as the infant Jesus, whose penis was sometimes emphasized for theological reasons, are other exceptions with elements of nudity in medieval religious fine art.

Belatedly Middle Ages [edit]

By the belatedly medieval menstruum female nudes intended to be attractive edged back into art, especially in the relatively private medium of the illuminated manuscript, and in classical contexts such as the Signs of the Zodiac and illustrations to Ovid. The shape of the female person "Gothic nude" was very unlike from the classical ideal, with a long body shaped by gentle curves, a narrow chest and high waist, small round breasts, and a prominent bulge at the stomach.[30] Male nudes tended to be slim and slight in figure, probably drawing on apprentices used as models, but were increasingly accurately observed.

Renaissance [edit]

During the Renaissance, involvement in the nude trunk in art was beingness rekindled after a thousand years. Toward the end of Greco-Roman antiquity, Christian doctrines of celibacy, chastity, and the devaluation of the flesh led to the declining interest of nudes for patrons, and thus for artists. Since the finish of the ancient classical menses, the unclothed body was only depicted in rare instances like renderings of Adam and Eve. Now, with the ascension of Renaissance humanism, Renaissance artists were relishing opportunities to depict the unclothed body.[31]

The reinvigoration of classical culture in the Renaissance restored the nude to art. Donatello made two statues of the Biblical hero David, a symbol for the Republic of Florence: his offset (in marble, 1408–1409) shows a clothed figure, but his 2d, probably of the 1440s, is the first freestanding statue of a nude since antiquity,[32] several decades before Michelangelo'due south massive David (1501–1504). Nudes in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling reestablished a tradition of male nudes in depictions of Biblical stories; the subject of the martyrdom of the near-naked Saint Sebastian had already become highly popular. The awe-inspiring female person nude returned to Western art in 1486 with The Nativity of Venus past Sandro Botticelli for the Medici family, who likewise owned the classical Venus de' Medici, whose pose Botticelli adapted.

Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) is considered past art historians to have been a pivotal figure in the resurgence of nudes in art because of his love of the aboriginal classical earth and how he incorporated classical principles of form into his creations.[33] He is not the first to utilize classical influences in his piece of work. However, few painters before him did this to the conspicuous degree and quality to which he did. He is known as a master of form, and his nudes are noteworthy because his style is influenced by his study of ancient classical sculpture and his knowledge of ancient classical Greek and Roman culture.[33] [34] The drawing of St. James Led to His Execution demonstrates that, early on, Mantegna did anatomical nude sketches in preparation for the Ovetari Chapel frescoes. This is the earliest known drawing past the creative person.[35]

The Dresden Venus of Giorgione (c. 1510), as well drawing on classical models, showed a reclining female person nude in a mural, outset a long line of famous paintings including the Venus of Urbino (Titian, 1538), and the Rokeby Venus (Diego Velázquez, c. 1650). Although they reflect the proportions of aboriginal statuary, such figures equally Titian's Venus and the Lute Histrion and Venus of Urbino highlight the sexuality of the female body rather than its ideal geometry. These works inspired endless reclining female nudes for centuries afterwards.[24] In addition to adult male and female person figures, the classical depiction of Eros became the model for the naked Christ kid.[31]

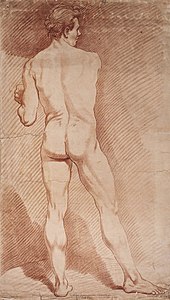

Raphael in his later on years is usually credited as the first artist to consistently use female models for the drawings of female figures, rather than studio apprentices or other boys with breasts added, who were previously used. Michelangelo'south suspiciously adolescent Study of a Kneeling Nude Daughter for The Entombment (Louvre, c. 1500), which is usually said to be the first nude female figure study, predates this and is an case of how fifty-fifty figures who would be shown clothed in the terminal work were often worked out in nude studies, so that the form under the vesture was understood. The nude figure drawing or effigy report of a live model speedily became an important part of artistic do and training, and remained so until the 20th century.

-

-

-

-

-

New year's Greeting with 3 Witches (1514) past Hans Baldung

17th and 18th centuries [edit]

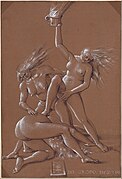

In Baroque art, the continuing fascination with classical antiquity influenced artists to renew and expand their approach to the nude, but with more than naturalistic, less idealized depictions, perhaps more frequently working from live models.[18] Both genders are represented; the male person in the form of heroes such as Hercules and Samson, and female in the form of Venus and the Three Graces. Peter Paul Rubens, who with evident delight painted women of generous figure and radiant mankind, gave his name to the adjective Rubenesque. While adopting the conventions of mythological and Biblical stories, Rembrandt's nudes were less idealized, and painted from life.[36] In the afterward Baroque or Rococo period, a more decorative and playful manner emerged, exemplified past François Boucher'south Venus Consoling Love, likely commissioned by Madame Pompadour.

Early modern [edit]

-

No. 37 of a set of 80 aquatint prints created by Goya in the 1810s depicting the horrors of war

-

La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Ingres

-

-

Goya's Nude Maja represent a break with the classical, showing a particular woman of his time, with pubic hair and a look directed at the viewer, rather than an allusion to nymphs or goddesses.

This year Venuses again... always Venuses!... (1864) by Daumier

In the 19th century the Orientalism movement added another reclining female nude to the possible subjects of European paintings, the odalisque, a slave or harem girl. Ane of the most famous was The Grande Odalisque painted by Ingres in 1814.[37] The almanac glut of paintings of idealized nude women in the Paris Salon was satirized by Honoré Daumier in an 1864 lithograph with the caption "This year Venuses again... always Venuses!... every bit if there really were women built like that!" While Europe accepted the nude in art, America was restrictive of sexuality, which sometimes included criticism or censorship of painting, even those that depicted classical or biblical subjects.[38]

In the after nineteenth century, academic painters connected with classical themes, but were challenged by the Impressionists. While the limerick is compared to Titian and Giogione, Édouard Manet shocked the public of his fourth dimension by painting nude women in contemporary situation in his Le Déjeuner sur fifty'herbe (1863); and although the pose of his Olympia (1865) is said to derive from the Venus of Urbino by Titian, the public saw a prostitute. Gustave Courbet similarly earned criticism for portraying in his Woman with a Parrot a naked prostitute without vestige of goddess or nymph.

Edgar Degas painted many nudes of women in ordinary circumstances, such as taking a bathroom.[39] Auguste Rodin challenged classical canons of idealization in his expressively distorted Adam.[40] With the invention of photography, artists began using the new medium as a source for paintings, Eugène Delacroix beingness one of the first.[18]

For Lynda Nead, the female person nude is a affair of containing sexuality; in the case of the classical art history view represented by Kenneth Clark, this is virtually idealization and de-emphasis of overt sexuality, while the modernistic view recognizes that the human body is messy, unbounded, and problematical.[41] If a virtuous adult female is dependent and weak, as was causeless by the images in classical art, then a strong, independent adult female could not be portrayed as virtuous.[42]

Late modernistic [edit]

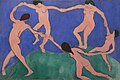

Although both the Academic tradition and Impressionists lost their cultural supremacy at the first of the twentieth century, the nude remained although transformed by the ideas of modernism. The arcadian Venus was replaced by the woman intimately depicted in individual settings, as in the work of Egon Schiele.[18] The simplified modernistic forms of Jean Metzinger, Amedeo Modigliani, Gaston Lachaise and Aristide Maillol call up the original goddesses of fertility more than than Greek goddesses.[43] In early abstract paintings, the body could be fragmented or dismembered, as in Picasso'southward Les Demoiselles d'Avignon or his structuralist and Cubist nudes, but there are as well abstracted versions of classical themes, such as Henri Matisse's dancers and bathers.

-

-

I Werners Eka (In Werner's Rowing Boat) (1917) by Anders Zorn

-

Suzanne Valadon was one of relatively few female artists in the early 20th century to pigment female nudes, as well as male nudes.[44] In 1916, she painted Nude Arranging her Hair, which depicts a woman carrying out a mundane chore in a frank, un-sexualised and not-erotic style.[44]

In the mail-WWII era, Abstract Expressionism moved the center of Western art from Paris to New York Urban center. One of the primary influences in the rise of abstraction, the critic Clement Greenberg, had supported de Kooning's early on abstruse work. Despite Greenberg'south advice, the creative person, who had begun as a figurative painter, returned to the human being course in early on 1950 with his Woman series. Although having some references to the traditions of single female person figures, the women were portrayed as voracious, distorted, and semi-abstract. Co-ordinate to the artist, he wanted to "create the angry humor of tragedy"; having the frantic look of the atomic age, a globe in turmoil, a world in need of comic relief. Subsequently, Greenberg added that "Maybe ... I was painting the woman in me. Art isn't a wholly masculine occupation, you lot know. I'one thousand enlightened that some critics would take this to be an access of latent homosexuality ... If I painted beautiful women, would that brand me a not-homosexual? I like beautiful women. In the flesh—even the models in magazines. Women irritate me sometimes. I painted that irritation in the Woman serial. That'due south all." Such ideas could not be expressed past pure brainchild alone.[45] Some critics, all the same, run into the Woman series as misogynistic.[46]

Other New York artists of this menstruum retained the effigy as their master subject. Alice Neel painted nudes, including her ain self-portrait, in the aforementioned straightforward style as clothed sitters,[47] being primarily concerned with color and emotional content.[48] Philip Pearlstein uses unique cropping and perspective to explore the abstruse qualities of nudes. As a immature creative person in the 1950s, Pearlstein exhibited both abstracts and figures, but it was de Kooning that advised him to continue with figurative work.[49]

Contemporary [edit]

Lucian Freud was one of a pocket-size group of painters which included Francis Bacon who came to be known equally "The School of London", creating figurative work in the 1970s when information technology was unfashionable.[51] All the same, by the end of his life his works had become icons of the Postmodern era, depicting the human body without a trace of idealization, equally in his series working with an obese model.[52] One of Freud's works is entitled "Naked Portrait", which implies a realistic image of a particular unclothed woman rather than a conventional nude.[53] In Freud's obituary in The New York Times, it is stated: His "stark and revealing paintings of friends and intimates, splayed nude in his studio, recast the art of portraiture and offered a new approach to figurative fine art".[54]

Around 1970, from feminist principles, Sylvia Sleigh painted a series of works reversing stereotypical artistic themes by featuring naked men in poses ordinarily associated with women.[55]

The paintings of Jenny Saville include family unit and self-portraits amidst other nudes; often washed in farthermost perspectives, attempting to balance realism with abstraction; all while expressing how a woman feels virtually the female nude.[56] Lisa Yuskavage'southward nude figures painted in a about academic manner constitute a "parody of art historical nudity and the male obsession with the female form equally object".[57] John Currin is another painter whose piece of work frequently reinterprets historic nudes.[58] Cecily Brown's paintings combine figurative elements and abstraction in a style reminiscent of de Kooning.[59]

The finish of the twentieth century saw the rise of new media and approaches to fine art, although they began much earlier. In particular installation art ofttimes includes images of the man trunk, and functioning art ofttimes includes nudity. "Cutting Piece" by Yoko Ono was first performed in 1964 (then known every bit a "happening"). Audience members were requested to come on stage and begin cutting away her habiliment until she was nearly naked. Several contemporary operation artists such as Marina Abramović, Vanessa Beecroft and Carolee Schneemann use their own nude bodies or other performers in their work.

Bug [edit]

Depictions of youth [edit]

In classical works, nude children were rarely shown except for babies and putti. Before the era of Freudian psychoanalysis, children were causeless to have no sexual feelings earlier puberty, so nude children were shown as symbols of pure innocence. Boys frequently swam naked, which was depicted in modern paintings past John Singer Sargent, George Bellows, and others. Other images were more than erotic, either symbolically or explicitly.[sixty] [61]

Gender differences [edit]

Representation of the world, like the world itself, is the work of men; they draw it from their own signal of view, which they misfile with absolute truth.

Men and women did not receive equal opportunities in artistic training from at least from the Renaissance until the middle of the nineteenth century. Women artists were not allowed access to nude models and could non participate in this part of the arts education.[62] [63] During this flow, study of the nude figure was something all male person artists were expected to go through to become an creative person of worth and to exist able to draw historical subjects.[64]

Academic fine art history tends to ignore the sexuality of the male nude, speaking instead of class and composition.[65]

For much of history, nude men represented martyrs and warriors, emphasizing an agile role rather than the passive one assigned to women in fine art. Alice Neel and Lucian Freud painted the modern male nude in the classic reclining pose, with the genitals prominently displayed. Sylvia Sleigh painted versions of classic works with the genders reversed.

Until the 1960s, art history and criticism rarely reflected anything other than the male point of view. The feminist art motion began to modify this, but i of the get-go widely known statements of the political letters in nudity was made in 1972 by the art critic John Berger. In Ways of Seeing, he argued that female person nudes reflected and reinforced the prevailing power relationship between females portrayed in art and the predominantly male audition. A year later on Laura Mulvey wrote Visual Pleasance and Narrative Cinema, in which she applied to pic theory the concept of the male person gaze, asserting that all nudes are inherently voyeuristic.[66]

The feminist art movement was aimed at giving women the opportunity to have their art reach the aforementioned level of notoriety and respect that men's art received. The idea that women are intellectually inferior to men came from Aristotelian ideology and was heavily depended on during the Renaissance. It was believed past Aristotle that during the process of procreation, men were the driving strength. They held all creative power while women were the receivers. Women's simply part in reproduction was to provide the fabric and act as a vessel. This idea carried over into the epitome of the creative person and the nude in art. The creative person was seen specifically equally a white male person, and he was the merely one who held the innate talent and creativity to exist a successful professional person creative person.[67] This conventionalities organization was prevalent in nude art. Women were depicted as passive, and they did not possess any control over their epitome. The female nude during the Renaissance was an paradigm created by the male gaze.[68]

In Jill Fields' commodity "Frontiers in Feminist Fine art History", Fields examines the feminist art move and its cess of female person nude imagery. She considers how the paradigm of the female nude was created and how the feminist art history move attempted to change the fashion the paradigm of the female nude was represented. Derived from the Renaissance platonic of feminine dazzler, the image of the female person trunk was created past men and for a male audition. In paintings like Gustave Courbet'due south The Origin of the Earth and François Boucher's Reclining Girl, women are depicted with open legs, implying that they are to be passive and an object to be used.[69] In A. West. Eaton's essay "What'south Wrong with the (Female) Nude? A Feminist Perspective on Art and Pornography", she discusses multiple ways in which the art of the female nude objectifies women. She considers how male nudes are both less common and represented equally agile and heroic, whereas female person nudes are significantly more prevalent and represent women as passive, vulnerable, sexual objects.[70] The feminist art history movement has aimed to change the style this prototype is perceived. The female nude has become less of an icon in Western art since the 1990s, but this reject in importance did not stop members of the feminist art movement from incorporating things like the "cardinal core" image.[71] This fashion of representing the nude female figure in art was focused on the fact that women were in control of their own prototype. The cardinal paradigm was focused on vulva-related symbols. By incorporating new images and symbols into the female nude image in Western fine art, the feminist fine art history movement continues to try and dismantle the male-dominated fine art globe.[68]

More recent discussion of the ceremoniousness of sure artworks has emerged in the context of the Me Too movement.[72]

Nudes depicting the female and queer gaze [edit]

Female person nudes accept long been informed by the male gaze, and men's desires of the nudity of women.[73] Feminist criticism has targeted female nudes, informed by the male person gaze, for nearly a century.[73] However, there are some artists who take turned this concept on its head, and accept, every bit a result, distilled the criticisms embodied within the male gaze nude depictions of women. Artists have instilled the female gaze in the nudes they create. Rather than women being the object of men'south desires, some artists have challenged traditional narratives of women, depicting them contrastingly equally being non-sexualised.[74]

Additionally, artists have implemented the queer gaze into fine art, and specifically nude art, which also challenges the traditional male gaze nude artwork.

- Helen Beard creates colourful and bright artwork in dissimilar mediums, from paintings, to needlepoint, to sculptures, depicting close ups of women in explicit, pornographic sexual positions.[75] Her pieces embody women feeling pleasured past their bodies, which contradicts the traditional male gaze nudes of women previously.[75]

- Lucy Liu has created a collection, entitled 'SHUNGA,' a Japanese term significant erotic art.[76] Liu's subject matter involves shut up images of lesbian women, entwined within each other and bed sheets.[76]

- Maggi Hambling recently commemorated the British feminist author, Mary Wollstonecraft, by creating A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft, which uses a nude female figure to represent the spirit of Wollstonecraft'south feminism.[77] This has caused cracking deals of controversy, with people questioning why Hambling chose to depict Wollstonecraft in nude class.[77] However, Hambling has argued that her reasoning is to draw Wollstonecraft every bit a spirit and a representation of every woman.[78]

- Louis Fratino has redefined the male person gaze and how queer men and women are represented in nude art.[79] His pieces explore queer sexuality in both everyday and erotic formats.[lxxx]

- Lisa Yuskavage's artwork has been included in The Female Gaze: Women Expect at Women exhibition in 2009.[81] Her work includes nude depictions of women, which illustrates the women as being incapable of caring what others recollect of them because of their own bodily discomfort, which does not brand them subjected to the male gaze.[82]

- Suzanne Valadon painted non-sexualised, not overly-erotic nude depictions of women.[83] The fine art work does non depict women from the traditional male person gaze standpoint, and Valadon was one of the merely women artists to paint such subject field thing, in such a way, in the offset half of the 20th century.[83]

Intersectionality [edit]

The nude epitome in art has affected women of color in a different way than it has white women, according to Charmaine Nelson. The unlike depictions of the nude in art has not only instituted a system of controlling the image of women only it has put women of color in a place of other. The intersection of their identities, as Nelson asserts, creates a "doubly fetishized black female torso". Women of colour are not represented to the degree that white women are in nude art from the Renaissance to the 1990s, and when they are represented information technology is in a different style than white women. The Renaissance ideal of female person beauty did non include black women. White women were represented as a sexual image, and they were the ideal sexual image for men during the Renaissance. White women, in about major works before the 20th century, did not have pubic hair. Black women normally did, and this created their image in an animalistic sexual way.[84] While the white women's image became 1 of innocence and the arcadian, black women were continually overtly sexualized, she adds.

[edit]

The nude has as well been used to make a powerful social or political statement. An example is The Barricade (1918) by George Bellows, which depicts Belgian citizens beingness used as human shields by Germans in World War I. Although based upon a report of a real incident in which the victims were non nude, portraying them so in the painting emphasizes their vulnerability and universal humanity.[85]

Media [edit]

A figure drawing is a report of the human being form in its various shapes and torso postures, with line, course, and limerick as the primary objective, rather than the discipline person. A life drawing is a piece of work that has been fatigued from an observation of a alive model. Study of the man effigy has traditionally been considered the best way to learning how to draw, commencement in the late Renaissance and continuing to the present.[86]

Oil paint historically has been the ideal medium for depicting the nude. By blending and layering pigment, the surface can become more like skin. "Its wearisome drying time and various degrees of viscosity enable the artist to reach rich and subtle blends of color and texture, which tin suggest transformations from one human substance to another."[87]

Due to its durability, it is in sculpture that we see the full, nearly unbroken history of the nude from the Stone Age to the present. Figures, usually of the naked female, have been found in the Balkan region dating back to 7,000 BCE[88] and continue to this day to exist generated. In the Indian and Southeast Asian sculpture tradition nudes were oftentimes adorned with bracelets and jewelry that tended to "punctuate their charms and demarcate the dissimilar parts of their bodies much equally developed musculature does in the male person".[89]

Photography [edit]

The nude has been a subject of photography almost since its invention in the nineteenth century. Early photographers often selected poses that imitated the classical nudes of the past.[90] Photography suffers from the problem of beingness also real,[91] [92] and for many years was non accepted by those committed to the traditional fine arts.[93] Nevertheless, many photographers have been established equally fine artists including Ruth Bernhard, Anne Brigman, Imogen Cunningham, Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston.

New media [edit]

In the late twentieth century several new art forms emerged, including installation, performance and video art, all of which have been used to create works that explore the concept of the nude.[94] An case is Mona Kuhn's site-specific installation Experimental (2018), which employs video projections, vinyl installation, and other mixed media.[95]

See besides [edit]

- Academic fine art – Style of painting and sculpture

- Artistic freedom – Freedom of expression and publication

- Body proportions – Proportions of the human body in art

- Artistic canons of body proportions – Criteria used in formal figurative fine art

- Depictions of nudity – Visual representations of the nude homo form

- Figurative art – Art that depicts existent object sources

- Effigy drawing – Cartoon of the human form

- Figure painting – Genre of painting that represents the human form

- The Helga Pictures – Series of paintings and drawings past Andrew Wyeth

- History of nudity – Social attitudes to nakedness

- History of erotic depictions – Aspect of history

- Model (fine art) – Person who poses for a visual artist

- Nude photography (art) – Creative photography of the naked homo body

- Vagina and vulva in art – Visual art representing female genitalia

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Michelangelo Gallery". Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ Clark 1956, Ch.1.

- ^ Alan F. Dixson; Barnaby J. Dixson (2011). "Venus Figurines of the European Paleolithic: Symbols of Fertility or Attractiveness?". Journal of Anthropology. 2011: 1–eleven. doi:10.1155/2011/569120.

- ^ Clark 1956, p. nine.

- ^ Nead 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Tomlinson & Calvo 2002, p. 228.

- ^ Bernheimer 1989.

- ^ "Ariadne Asleep On The Isle Of Naxos". New-York Historical Social club. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Eck 2001.

- ^ Clark 1956, pp. 8–nine.

- ^ Nead 1992.

- ^ Dijkstra 2010, p. 11.

- ^ Dijkstra 2010, Introduction.

- ^ Steiner 2001, pp. 44, 49–l.

- ^ "Trunk Language: How to Talk to Students about Nudity in Art" (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. March xviii, 2003. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Borzello 2012, Introduction.

- ^ Borzello 2012, Ch. 2 – Body Fine art: the Journey into Nakedness.

- ^ a b c d Graves 2003.

- ^ a b c Sorabella 2008a.

- ^ a b Asher-Greve & Sweeney 2006.

- ^ Davis, Frank (June 13, 1936). "A puzzling "Venus" of 2000 B.C.: a fine Sumerian relief in London". The Illustrated London News. 1936 (5069): 1047.

- ^ Patai, Raphael (1990). The Hebrew Goddess (3d ed.). Detroit: Wayne State Academy Printing. ISBN0-8143-2271-9.

- ^ Bonfante 1989.

- ^ a b c Rodgers & Plantzos 2003.

- ^ Hay 1994.

- ^ Esanu 2018, Ch. two.

- ^ Clark 1956, pp. 300–309.

- ^ Ryder 2008.

- ^ Clark 1956, pp. 221–226.

- ^ Clark 1956, pp. 307–312.

- ^ a b Sorabella 2008b.

- ^ Clark 1956, pp. 48–50.

- ^ a b Kristeller, Paul (1901). Andrea Mantegna. London: Logmans, Green, and Company. pp. 106–107, 140, 143, 233–234.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio. "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Lives Of The Most Eminent Painters Sculptors And Architects". www.gutenberg.org . Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ "drawing: Study for the Ovetari Chapel". British Museum. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Sluijter 2006, Introduction.

- ^ "Ingres' La K Odalisque".

- ^ D'Emilio & Freedman 2012, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Shackelford & Rey 2011.

- ^ Sorabella 2008c.

- ^ Nead 1992, Office I – Theorizing the Female Nude.

- ^ Dijkstra 2010, Ch. three.

- ^ Borzello 2012, p. 30.

- ^ a b "Nude Arranging Her Pilus | Artwork". NMWA. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Scala, Ch 2. "The Influence of Anxiety" by Susan H. Edwards

- ^ Monaghan 2011.

- ^ Leppert 2007, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Borzello 2012, Chapter 2 – The Changing Room: Female Perspectives.

- ^ Borzello 2012, p. 90.

- ^ Legacy Staff 2011.

- ^ Riding, Alan (September 25, 1995). "The School of London, Mordantly Messy equally Ever". The New York Times . Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Lucian Freud at the National Portrait Gallery – in pictures". The Guardian. London. February 8, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ The Tate Modern 2013.

- ^ Grimes, William (July 22, 2011). "Lucian Freud, Figurative Painter Who Redefined Portraiture, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times.

- ^ Leppert 2007, pp. 221–223.

- ^ "Jenny Saville". Saatchi Gallery. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ Mullins 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Mullins 2006, p. 168.

- ^ Mullins 2006, p. 35.

- ^ Dijkstra 2010, Ch. 5.

- ^ Leppert 2007, Ch. 2.

- ^ Myers, Nicole. "Women Artists in Nineteenth–Century France". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Levin, Kim (November 1, 2007). "Top X ARTnews Stories: Exposing the Hidden 'He'". ARTnews.

- ^ Nochlin 1988.

- ^ Leppert 2007, p. 166.

- ^ Leppert 2007, pp. nine–eleven.

- ^ Jacobs 1994.

- ^ a b McDonald 2001.

- ^ Hammer-Tugendhat & Zanchi 2012, pp. 361–382.

- ^ Maes & Levinson 2015.

- ^ Fields 2012.

- ^ Stewart-Kroeker 2020.

- ^ a b Eaton, A. Due west. "What's Incorrect with the (Female) Nude? A Feminist Perspective on Fine art and Pornography." Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art: The Analytic Tradition, An Anthology (2018): 266.

- ^ "Women Artists: The Female person Gaze". Pallant Business firm Gallery . Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Helen Beard". METAL . Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Lucy Liu | Art | Shunga". Lucy Liu . Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "People Are Understandably Furious Over This New Naked Statue of Pioneering Feminist Mary Wollstonecraft in London". Artnet News. November x, 2020. Retrieved April seven, 2021.

- ^ "Mary Wollstonecraft statue becomes 1 of 2020s most polarising artworks". The Guardian. Dec 25, 2020. Retrieved April seven, 2021.

- ^ Sargent, Antwaun (September 17, 2018). "These Gay Figure Artists Are Reimagining the Male person Gaze". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "Queer Artist Louis Fratino Discusses the New Age of Gay Civilization". L'Officiel USA. March 11, 2021. Retrieved Apr seven, 2021.

- ^ "The Female Gaze, Part Two: Women Await at Men". Cheim Read.

- ^ Wye, Pamela (1997). "Desiring Machines and Exquisite Corpulence: Lisa Yuskavage's Girlies". Clayton Eshleman, ed & Pub. 40: 101.

- ^ a b "Nude Arranging Her Hair | Artwork". NMWA . Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ Nelson 1995.

- ^ Dijkstra 2010, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Nicolaides 1975.

- ^ Scala 2009, p. i.

- ^ Gimbustas 1974.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Dawes 1984, p. 6.

- ^ MOMA 2012.

- ^ Scala 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Clark 1956.

- ^ Daris 2016.

- ^ Hamilton 2018.

References [edit]

Books [edit]

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Sweeney, Deborah (2006). "On Nakedness, Nudity, and Gender in Egyptian and Mesopotamian Art". In Schroer, Sylvia (ed.). Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen: Academic Printing Fribourg.

- Borzello, Frances (2012). The Naked Nude. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-23892-nine.

- Burke, Jill (2018). The Italian Renaissance Nude. Yale University Press. ISBN978-030020156-seven.

- Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude: A Written report in Platonic Form . Princeton University Press. ISBN0-691-01788-3 – via Internet Annal.

- D'Emilio, John; Freedman, Estelle B. (2012). Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (Tertiary ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-92380-2.

- Dawes, Richard, ed. (1984). John Hedgecoe's Nude Photography. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-017006531-3.

- Dijkstra, Bram (2010). Naked: The Nude in America. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN978-0-8478-3366-5.

- Dutton, Denis (2009). The Art Instinct: Dazzler, Pleasure, and Man Evolution. New York: Bloomsbury Printing. ISBN978-1-59691-401-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Esanu, Octavian, ed. (2018). Fine art, Enkindling, and Modernity in the Eye Due east: the Arab Nude. New York City: Routledge.

- Gill, Michael (1989). Epitome of the Body. New York: Doubleday. ISBN0-385-26072-five.

- Gimbustas, Marija (1974). The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN978-052001995-9.

- Goldberg, Vicki (2000). Nude Sculpture: 5,000 Years. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN978-081093346-0.

- Hausenstein, Wilhelm (1913). Der nackte Mensch der Kunst aller Zeiten und Völker. Munich: R. Riper & Co.

- Hay, John (1994). "The Body Invisible in Chinese Art?". In Zito, Angela; Barlow, Tani Due east. (eds.). Subject, and Power in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 42–77. ISBN978-022698727-9.

- Hughes, Robert (1997). Lucian Freud Paintings. Thames & Hudson. ISBN0-500-27535-1.

- Jacobs, Ted Seth (1986). Drawing with an Open Heed. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN0-8230-1464-9.

- Jullien, François (2007). The Impossible Nude: Chinese Art and Western Aesthetics. Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN978-0-226-41532-one.

- King, Ross (2007). The Judgement of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade that Gave the World Impressionism. PIML. ISBN978-ane-84413-407-6.

- Leppert, Richard (2007). The Nude: The Cultural Rhetoric of the Body in the Fine art of Western Modernity. Cambridge: Westview Printing. ISBN978-0-8133-4350-i.

- LeValley, Paul (2016). Art Follows Nature: A Worldwide History of the Nude. Berkeley: Edition One Books. ISBN978-099926790-v. OCLC 965382008.

- Maes, Hans; Levinson, Jerrold, eds. (July ii, 2015). Art and pornography: philosophical essays. ISBN978-019874408-5. OCLC 965117928.

- McDonald, Helen (2001). Erotic Ambiguities: The Female Nude in Art. Routledge. ISBN978-041517099-four.

- Mullins, Charlotte (2006). Painting People: Figure Painting Today. New York: D.A.P. ISBN978-1-933045-38-ii.

- Nead, Lynda (1992). The Female Nude. New York: Routledge. ISBN0-415-02677-vi.

- Nicolaides, Kimon (1975). The Natural Way to Draw. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN0-395-20548-four.

- Nochlin, Linda (1988). Women, Fine art and Ability and Other Essays. Thames and Hudson. ISBN978-006435852-ane.

- Postle, G.; Vaughn, W. (1999). The Artist'due south Model: from Etty to Spencer. London: Merrell Holberton. ISBN1-85894-084-2.

- Rosenblum, Robert (2003). John Currin. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN0-8109-9188-8.

- Saunders, Gill (1989). The Nude: A New Perspective. Rugby, Warwickshire, England: Jolly & Barber. ISBN0-06-438508-vi.

- Scala, Marker, ed. (2009). Paint Made Flesh. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN978-0-8265-1622-0.

- Shackelford, George T. M.; Rey, Xavier (2011). Degas and the Nude. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. ISBN978-087846773-0.

- Sluijter, Eric Jan (2006). Rembrandt and the Female person Nude. Amsterdam University Printing. ISBN978-905356837-8.

- Smith, Alison; Upstone, Robert (2002). Exposed: the Victorian Nude. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications.

- Steiner, Wendy (2001). Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century Art. The Costless Press. ISBN0-684-85781-2.

- Steinhart, Peter (2004). The Undressed Art: Why Nosotros Describe. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN1-4000-4184-8 – via Internet Archive.

- Tomlinson, J. A.; Calvo, Southward. F. (2002). Goya: Images of women. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ISBN0-89468-293-8.

- Walters, Margaret (1978). The Nude Male: A New Perspective. New York: Paddington Press. ISBN0-448-23168-nine – via Internet Annal.

- Wilcox, Jonathan (2003). Naked before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England. Medieval European Studies. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Journals [edit]

- Bernheimer, Charles (Summertime 1989). "Manet's Olympia: The Figuration of Scandal". Poetics Today. 10 (ii): 255–277. doi:10.2307/1773024. JSTOR 1773024.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1989). "Nudity every bit a Costume in Classical Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 93 (4): 543–570. doi:10.2307/505328. JSTOR 505328.

- Eck, Beth A. (2001). "Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity". Sociological Forum. xvi (4): 603–32. doi:10.1023/A:1012862311849. S2CID 143370129.

- Fields, Jill (2012). "Frontiers in Feminist Art History". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 33 (2): 1–21. doi:ten.5250/fronjwomestud.33.2.0001. S2CID 142427676.

- Hammer-Tugendhat, Daniela; Zanchi, Michael (2012). "Art, Sexuality, and Gender Structure". Art in Translation. 4 (iii): 361–382. doi:ten.2752/175613112X13376070683397. S2CID 193129278.

- Jacobs, Frederika H. (1994). "Woman's Chapters to Create: The Unusual Case of Sofonisba Anguissola". Renaissance Quarterly. 47 (ane): 74–101. doi:10.2307/2863112. JSTOR 2863112.

- Nelson, Charmaine (1995). "Coloured Nude: Fetishization, Disguise, Dichotomy". RACAR: Revue d'fine art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 22 (i–two): 97–107. doi:x.7202/1072517ar.

- Nochlin, Linda (1986). "Courbet's "L'origine du monde": The Origin without an Original". October. 37: 76–86. doi:x.2307/778520. JSTOR 778520.

- Stewart-Kroeker, Sarah (2020). "What Exercise Nosotros Practise with the Art of Monstrous Men?". De Ethica. vi (ane): 51–74. doi:ten.3384/de-ethica.2001-8819.19062502.

News [edit]

- Guardian (February 8, 2012). "Lucian Freud at the National Portrait Gallery – in pictures". The Guardian. London. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Conrad, Donna (2000). "A Conversation with Ruth Bernhard". PhotoVision. Vol. one, no. iii.

- Daris, Gabriella (February one, 2016). "Six Dance Shows Stripped Blank: Redefining Nudity on Stage". Artinfo. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016.

- Gopnik, Blake (November viii, 2009). "In Fine art We Lust". The Washington Postal service . Retrieved Feb 23, 2013.

- Grimes, William (July 22, 2011). "Lucian Freud, Figurative Painter Who Redefined Portraiture, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times.

- Monaghan, Peter (January 2, 2011). "Unveiling the American Nude". The Chronicle of Higher Teaching.

- Riding, Alan (September 25, 1995). "The School of London, Mordantly Messy as Ever". The New York Times . Retrieved Feb xvi, 2013.

- Schjeldahl, Peter (June ix, 2008). "Funhouse: A Jeff Koons retrospective". The New Yorker . Retrieved Feb 24, 2013.

Spider web [edit]

- Department of Museum Didactics (March xviii, 2003). "Body Linguistic communication: How to Talk to Students well-nigh Nudity in Fine art" (PDF). Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Graves, Ellen (2003). "The Nude in Art – a Cursory History". University of Dundee. Retrieved July fifteen, 2020.

- Hamilton, Julie (October ii, 2018). "Mona Kuhn Turns Apartment Photos into an Immersive Surroundings". INDY Week . Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- Legacy Staff (July 22, 2011). "Lucian Freud painted people "how they happen to exist"".

- MOMA (2012). "Naked Earlier the Photographic camera". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Postiglione, Corey. "The Postmodern Nude". Brad Cooper Gallery. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Rodgers, David; Plantzos, Dimitris (2003). Nude. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-188444605-4.

- Ryder, Edmund C. (January 2008). "Nudity and Classical Themes in Byzantine Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- "Jenny Saville". Saatchi Gallery. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008a). "The Nude in Western Art and its Beginnings in Antiquity". Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved July xv, 2020.

- Sorabella, Jean (Jan 2008b). "The Nude in the Centre Ages and the Renaissance". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Sorabella, Jean (January 2008c). "The Nude in Baroque and Later Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Fine art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Naked Portrait 1972-three". The Tate Mod. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- "Edward Weston". Edward-Weston.com . Retrieved July 19, 2020.

Further reading [edit]

- Falcon, Felix Lance (2006). Gay Art: a Historic Collection [and history], ed. and with an introd. & captions past Thomas Waugh. Vancouver, B.C.: Arsenal Lurid Press. N.B.: The art works are b&w sketches and drawings of males, nude or virtually and then, with much commentary. ISBN 1-55152-205-v

- Natter, Tobias Yard.; Leopold, Elisabeth, eds. (2012). Nude Men: From 1800 Until the Present Day. Munich: Hirmer Publishers. ISBN978-three-7774-5851-ix.

- Roussan, Jacques de (1982). Le Nu dans 50'art au Québec. La Prairie, Qué.: Éditions G. Broquet. N.B.: Concerns mostly the creative depiction of the female nude, primarily in painting and drawing. ISBN 2-89000-066-4

External links [edit]

- "Francis Bacon". Estate of Francis Bacon. Retrieved November ten, 2012.

- Leopold Museum, Republic of austria -Nude Men

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nude_(art)

0 Response to "free 3d nude female medieval warriors pictures and drawings.net free"

Post a Comment